455

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

Nepal, a small country with an area of 147,181 square kilometers, has a population of 28.98 million (WB, 2016). Nepal is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of bio-diversity due to its geographical position (NTB, 2003). The elevation of the country ranges from 70 m above sea level to the highest point on the earth, Mt. Everest at 8,848 m, all within a breadth of 150 km with climatic conditions ranging from subtropical to arctic. The wild variation fosters an incredible variety of ecosystems, the greatest mountain range on the earth, thick tropical jungles teeming with a wealth of wildlife, thundering rivers, forested hills and frozen valleys. Nepal’s natural attractions are ranging from physical, historical, cultural monuments, temples, art treasures and festivals (DOT, 1972). Nepal’s diversity attracts tourists. Its physical uniqueness offers a wide scope of activities that range from jungle safaris to trekking in snow-capped mountains. Tourism is important to Nepal as a source of foreign exchange and a major employment generator. For a country like Nepal, which lacks abundant resources, the tourism sector is expected to continue to play an important role in the country’s development, but not without negative consequences (Kunwar & Pandey, 1995). Etymologically, the word tour is derived from the Latin ‘tornare’ and the Greek ‘tornos’, meaning a lathe or circle; the movement around a central point or axis. This meaning changed in Modern English to represent one’s turn. The suffix ‘ism’ is defined as ‘an action or process; typical behavior or quality’, while the suffix ‘ist’ denotes ‘one that performs a given action’. When the word tour and the suffixes ‘ism’ and ‘ist’ are combined, they suggest the action of movement around a circle. One can argue that circle represents a starting point, which ultimately returns to its beginning. Therefore, like a circle tour represents a journey that is a round- trip, i.e., the act of leaving and then returning to the original starting point, and therefore, one who takes such a journey can be called a tourist (Theobald, 1997). Hospitality has been one of the most pervasive metaphors within tourism, referring in one sense to the commercial projects of the tourist industry such as hotels, catering, and tour operation, and in another sense, to the social interactions between local people and tourists, i.e., hosts and guests (Germann & Gibson, 2007). Social hospitality can be defined as the social setting in which hospitality and acts of hospitableness takes place together with the impacts of social forces on the production and consumption of food, drink and accommodation (Thio, 2005). Event is an important motivator of tourism, and figure prominently in the development and marketing plans of most destinations. The roles and impacts of planned events within tourism have been well documented, and are of increasing importance for destination competitiveness. Yet it was only a few decades ago that ‘event tourism’ became established in both the tourism industry and in the research community, so that subsequent growth of this sector can only be described as spectacular (Getz, 2007). Security is taken to be about the pursuit of freedom from threat and the ability of states and societies to maintain their independent identity and their functional integrity against the forces of change, which they see as hostile. The bottom line of security is survival, but it also reasonably includes a substantial range of concerns about the conditions of existence. Quite where this range of concerns ceases to merit the urgency of the “security” label and becomes part of everyday uncertainties of life is one of the difficulties of the concept (Buzan, 1991). Security implies a stable, relatively predictable environment in which an individual or group may pursue its ends without disruption or harm and without fear of such disturbance or injury (Fisher, 2004). The interrelationships between tourism and security have been interpreted largely negatively. This is because as a universal phenomenon falling under the integral part of globalization, tourism seeks peace, stability and tranquility in guest, host and also transit destinations for its operations, managements, and growths (Hall & Sullivan, 1996; Tarlow, 2006). As the home to world’s highest mountains in a multi-ethnic federal democratic republic setup, Nepal is a popular tourist destination for adventure, recreation and ecotourism. Tourism is one of the most cherished inspirations for peace and prosperity in Nepal. Nevertheless, a number of security related factors. The sporadic political conflicts, instabilities, strikes, social unrests, and the disputes between Nepal-India at the border area at present are ongoing manmade security challenges appearing from wider external environments (Upadhaya, 2016). To formulate and construct the basis for a theory of tourism security it is necessary, first, to define the major concepts that are derived from the relationship between tourism and security incidents. Once these concepts and their respective variables are defined they will lay the foundations for the theoretical development of empirical generalizations. This challenging task involved the creation of the first two fundamental building blocks of the theory. The chapter started with a construction of tourism and security concepts and their corresponding variables as the first building block. Subsequently, as the second block, it assembled a wide array of empirical generalizations that represent the current best practices in the field of tourism security (Mansfeld, 1996). Tourism security refers to the measures and strategies that are implemented to mitigate security risks in the tourism industry. Effective tourism security requires a comprehensive and integrated approach, involving multiple stakeholders, including governments, tourism industry organizations, law enforcement agencies, and local communities. Tourism security measures can include the implementation of security protocols and procedures, the deployment of security personnel and technology, and the provision of information and awareness-raising programs for tourists. The Nepalese government has also established the Department of Tourism and other agencies responsible for tourism security. These agencies work closely with local communities, tourism industry stakeholders, and law enforcement agencies to develop effective security strategies that promote safe and sustainable tourism. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of effective tourism security in promoting safe and sustainable tourism. The Nepalese government has recognized the need to adapt and develop new strategies to address emerging security risks and ensure that tourists can travel safely and securely. The tourism industry's stakeholders, including tour operators, hoteliers, and local communities, have also played a critical role in implementing these measures and promoting responsible tourism practices. Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought about significant changes to tourism security in Nepal. However, by implementing effective security measures and strategies, Nepal can continue to attract tourists and promote safe and sustainable tourism in the post-pandemic era.

Objective

The specific objective of the study is to analyze the variation of tourism and security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal. In order to meet the objective of the research the following alternative hypothesis has been stated.

Hypothesis 1: There is significant association between independent variables of tourism security as prior to COVID-19.

Hypothesis 2: There is significant association between independent variables of tourism security in post COVID-19.

Hypothesis 3: There is significant variation of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Tourism Security as prior to COVID-19

Tourism is one of the most important industries in Nepal, and the country has experienced a steady increase in the number of tourists over the past few decades. However, as with any popular tourist destination, there are concerns about the safety and security of visitors. This literature review will explore the current state of research on tourism security in Nepal. Satyal (1988) expounded that, “generally, tourism denotes the movement or journey of Human beings from one place to another, whether it is within own country or other countries, for various purposes. The popular word Tourism of the present day is derived from the French word tourisme is related to travel and travel related activities. Later, this word was popularized in the 1930s, but its significance was not fully realized until recent times when Tourism has a wider meaning and significance”. According to (Negi,1990). “Tourism is the movement of the people from one place to another or one country to another at leisure for the purpose of pleasure, business, religion, health treatment or visiting friends and relatives. Tourism is also mentioned in Sanskrit, in ancient times. In Sanskrit literature, there are three terms for tourism, derived from the root ‘atna’, which means going or leaving home for some other place”. Buzan, (1991) illustrated that, ‘Security is taken to be about the pursuit of freedom from threat and the ability of states and societies to maintain their independent identity and their functional integrity against forces of change, which they see as hostile. Th e bottom line of security is survival, but it also reasonably includes a substantial range of concerns about the conditions of existence. Quite where this range of concerns ceases to merit the urgency of the “security” label and becomes part of everyday uncertainties of life is one of the difficulties of the concept’. Mansfeld, (1996) stated that, “to formulate and construct the basis for a theory of tourism security it is necessary, first, to define the major concepts that are derived from the relationship between tourism and security incidents. Once these concepts and their respective variables are defined they will lay the foundations for the theoretical development of empirical generalizations. This challenging task involved the creation of the first two fundamental building blocks of the theory. The chapter started with a construction of tourism and security concepts and their corresponding variables as the first building block. Subsequently, as the second block, it assembled a wide array of empirical generalizations that represent the current best practices in the field of tourism security”. According to Prizam, (1996) “tourism security theory is a research agenda that develops scientific knowledge in two distinctive directions. The first research direction is to conduct a set of studies examining the relationship between tourism and security on a destination-specific basis. The aim of this direction is to further deepen the understanding of causes and effects in tourism and security relations. The second research direction is to encourage the conduct of comparative (i.e., local, regional, national, international) studies to test the level of universalism of the proposed tourism security theory”. Paudyal, (1999) in his doctoral studies entitled “Factors Affecting Demand for Tourism in SAARC Region” has pointed out that there are many factors negatively affecting the tourism development in Nepal e.g. pollution problems, transport bottlenecks, skilled guide and low-quality tourist products. Shrestha, (1998) in his doctoral studies on “Tourism Marketing in Nepal” has precisely highlighted the challenges of tourism marketing in Nepal. His main findings were that Nepal is extremely rich in tourism products and it exists all over the country. Natural wealth, cultural and monumental heritage bequeathed history are the principal tourism products of Nepal. Further he analyzed that tourism is a major source of foreign exchange of Nepal and it is playing an important role in the national economy. Tourism helps to promote balance of payment and balance regional development of the country as well. Aryal, (2002) in his thesis on the topics the problems and Prospects of Tourism Development in Nepal”, he found from his study the total tourist arrival is in increasing trend. Mainly tourists arrived in Nepal for six purposes such as: pleasure, Trekking and mountaineering, Business, official, Pilgrimage meeting and Seminar and others. And he further found that the young tourists are very much interested to visit Nepal. George, (2003) described that, if a tourist feels unsafe or threatened at a holiday destination; he or she can develop a negative impression of the destination. This can be damaging to the destination’s tourism industry and can result in the decline of tourism to the area. Aryal, (2005) made a study on the topic of “Economic Impact to Tourism in Nepal”. His focus of study is as to study the trend of tourist arrivals in the country, contribution of tourism sector to the GDP, foreign currency earning through tourism and to review the tourism policy in Nepal. Aryal’s study is completely based on the secondary information and uses regression analysis. This provided guidelines for development methodology for the present study. According to Iswani, (2006) safety and security in tourism can be considered as safety in a destination either in urban area or rural area. In urban area, the case like crime, pick pocketing, kidnapping, rape and others always happen to people especially foreigner. While the safety in rural or natural area always exposed to natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, and landslides. Bentley, (2006) illustrated that, ‘in mountain-based adventure tourism activity, tourist injuries are the major problems occur in this activity. For instance, New Zealand recorded the high number of death cases involving foreigners taking part in adventure and recreational tourism activities such as major incidents in scenic flights, white water rafting, jet boating and tramping and mountaineering’. Gibson, (2007) stated that, Hospitality has been one of the most pervasive metaphors within tourism studies, referring in one sense to the commercial project of the tourist industry such as hotels, catering, and tour operation, and in another sense, to the social interactions between local people and tourists, that is, hosts and guests. Dahal, (2007) described that, ‘apart of attractions, proper accommodations, accessibility (convenient and easy access), and attractive tourism packages considering cost comparisons; safety and security are dominantly non-compromise-able elements for the tourists’ visitation decisions. Tourism which is also called as a peace and development industry cannot thrive in insecure environment’. Upadhayay, (2008) explained in his article “Rural Tourism to create equitable and growing Economy in Nepal” defines, “Rural tourism is a complex multifaceted activity. It is not just farm based tourism. It concludes farm-based holidays, eco-tourism, walking, climbing, adventure, sports, health tourism, hunting, fishing, educational art and heritage tourism like, to achieve maximum human welfare and happiness, through sustainable socioeconomic development of rural area, to reduce regional inequality and economic disparities and to contribute in poverty alleviation. Tarlow, (2014) truly brought out that, “the interrelationships between tourism and security have been interpret-rated largely negatively. This is because as a universal phenomenon falling under the integral part of globalization, tourism seeks peace, stability and tranquility in guest, host and also transit destinations for its operations, managements, and growths”. A study by Basnet & Gurung, (2017) found that the most common types of theft experienced by tourists in these areas were pick pocketing and bag snatching. The study also identified a lack of awareness among tourists about the risk of theft and the need to take precautions. Kunwar, (2017) rationally reflected that, while theorizing hospitality, Lynch el al. (2011) write, “rather than assuming that hospitality entails a particular context (such as the home or hotel) or particular objects (such as food and beds) or particular actors (such as host and guests), we see hospitality as both a condition and an effect of social relations, spatial configurations and power structures”. A study by Bhandari, (2018) found that the 2015 earthquake in Nepal had a negative impact on the tourism industry, and that political instability and security concerns were also contributing factors. The study recommended that the government and tourism industry work together to improve security and reduce the risk of political instability. A study by Dhungana et al, (2019) found that tourists were generally aware of the risk of earthquakes in Nepal, but were less aware of the risk of landslides. The study also identified a need for better communication and coordination between tourism stakeholders and local authorities in the event of a natural disaster. A study by Acharya & Gurung, (2019) found that tourists were at risk of theft, and the lack of awareness among tourists about the risk of theft was identified as a major factor. The study recommended the development of effective security measures and awareness-raising campaigns to mitigate this risk. A study by Shakya & Maharjan, (2019) found that tourists in Nepal may experience harassment and discrimination based on their gender or ethnicity. The study recommended the development of more inclusive policies and practices in the tourism industry to address these issues. In conclusion, tourism security in Nepal before the COVID-19 pandemic was a multifaceted issue that involved a variety of factors, including theft, natural disasters, political instability, and cultural and social factors. The literature has emphasized the need for effective risk communication, security measures, and inclusive policies and practices to ensure the safety and security of tourists in Nepal.

Tourism Security in post COVID-19

Tourism is one of the most thriving industries in Nepal. The snow-capped mountains, a rich diversity of cultures, scenic places, rivers, lakes, flora and fauna, historical monuments, bilingual and hospitable people are the main attractions for the foreign visitors. Nepal has immense diversity in natural and socio-cultural aspects. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the tourism industry worldwide, including in Nepal. The literature on tourism security in Nepal after the pandemic has focused on how the country can safely reopen its tourism industry while mitigating the risk of COVID-19 transmission. A study by Adhikari and Adhikari (2020) recommended the use of temperature checks, health questionnaires, and testing for COVID-19 upon arrival in Nepal. The study also emphasized the need for strict enforcement of quarantine measures for infected or suspected cases. A study by Gyawali & Basnet, (2020) found that political instability had a negative impact on tourism in Nepal, and that terrorism was a potential threat to tourist safety. The study recommended the development of effective security measures and the improvement of political stability to support the tourism industry. A study by Adhikari et al., (2020) found that tourists in Nepal may experience cultural shock and discrimination based on their ethnicity or gender. The study recommended the development of more inclusive policies and practices in the tourism industry to address these issues. A study by Paudel et al., (2020) emphasized the importance of hand hygiene, social distancing, and the use of personal protective equipment for tourism workers. The study also recommended the use of disinfection measures for tourist sites and accommodations. A study by Adhikari & Adhikari, (2020) found that the COVID-19 pandemic had a severe impact on the tourism industry, and effective crisis management protocols were essential to ensure the safety of tourists. The study recommended the development of hygiene and sanitation measures, communication and education for tourists, and screening protocols to mitigate the risk of the pandemic. In recent years, health-related issues, particularly COVID-19, have become a major concern for tourism security in Nepal. The literature has emphasized the need for effective screening, hygiene and sanitation measures, communication and education for tourists, and crisis management protocols to ensure the safety and security of tourists in Nepal during the pandemic (Adhikari and Adhikari, 2020; Paudel et al., 2020; Gurung and Basnet, 2021; Poudel et al., 2021). A study by Gurung and Basnet, (2021) found that tourists in Nepal were generally aware of the need to take precautions to prevent COVID-19 transmission, but there was a need for better communication and education about specific measures. A study by Pant et al., (2021) found that tourists in Nepal were generally aware of the risk of earthquakes, but less aware of the risk of landslides. The study recommended the development of effective risk communication strategies and the improvement of infrastructure to mitigate the impact of natural disasters on tourism. A study by Poudel et al, (2021) recommended the development of a national tourism crisis management plan for Nepal, with clear protocols for responding to future crises. In conclusion, the literature on tourism security in Nepal after the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the need for effective screening, hygiene and sanitation measures, communication and education for tourists, and crisis management protocols. As Nepal works to safely reopen its tourism industry, these measures will be crucial in ensuring the safety and security of tourists and tourism workers.

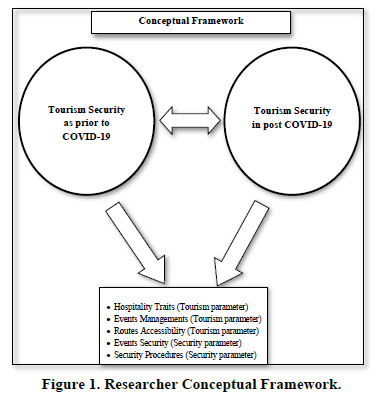

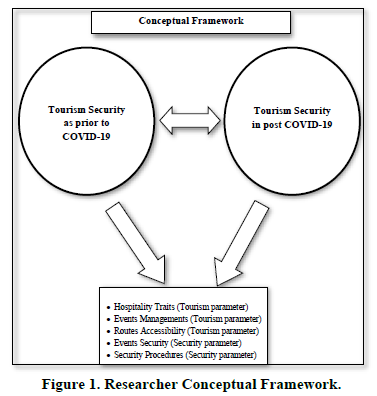

Conceptual Framework

The study of analyzing variation of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 is a virgin study in the field of tourism security in Nepal. By assessing the literature of prior and post COVID-19 circumstances the following conceptual framework has been have been developed (Figure 1).

METHODOLOGY

In order to analyze variation of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal, the research follows a sequential explanatory research design with quantitative approach to test the hypothesis. Both primary data and secondary data are extracted to generalize the concept. Primary data are extracted from stratified sampling technique using five-point Likert- scales questionnaire and secondary data are books, newspaper, articles, reports and internet explorer. The five-point Likert- scales questionnaire was constituted to measure the tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal with their independent variables. Altogether, 65 questionnaires were distributed to policymakers, tourism industry stakeholders, security personnel and tourists for survey and approximately 77% responses have been achieved. The study uses mean, standard deviations, standard error and correlation analysis with the help of statistical package for social science (SPSS).

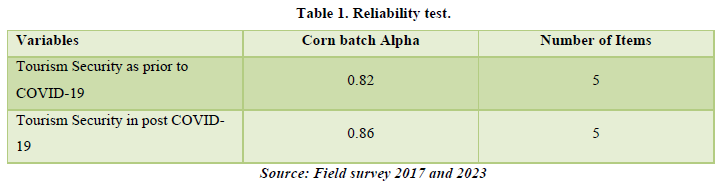

In order to measure different independent variables of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal, Likert scale values 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are taken as ‘Strongly disagree’, ‘Disagree’, ‘Neutral’, ‘Agree’, and ‘Strongly agree’ respectively. The value 3 is neutral. This means that the mean score of value 3 indicates no effect of variable. The primary data in the survey are collected from concern offices. The reliabilities of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal are tested in seven independent variables. The variables and their values of Cronbach's alpha are given below (Table 1).

The result shows the value of corn batch alpha for tourism security as prior to COVID-19 and Tourism Security in post COVID-19 are 0.82 and 0.86 respectively. The alpha value above 0.7 is considered as a reliable for inferential analysis. At this level and higher, the items are sufficiently consistent to indicate the measure is reliable.

Findings and Analysis

The findings are sequenced according to the research hypothesis. The first hypothesis and second hypothesis assume there is significant association between Independent variables of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal respectively. The responses of all independent variables of shown in descriptive value and after computing the variables, correlation test is conducted to measure the coefficient and significant. The third hypothesis assumes there is variation of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal. Both variables are correlated with each other and correlation test conducted.

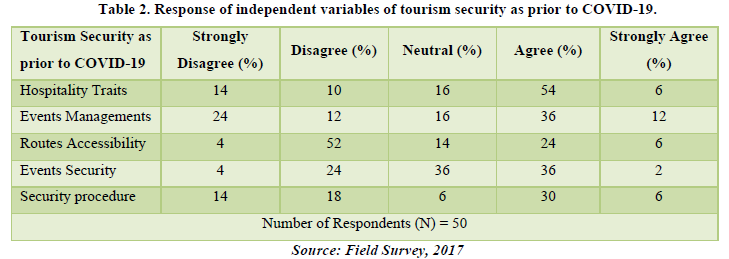

Tourism Security as prior to COVID-19

The variables are the determinant factors for the tourism security as prior to COVID-19 in Nepal are extracted from different literature review as mention above. The results of the responses are shown below (Table 2).

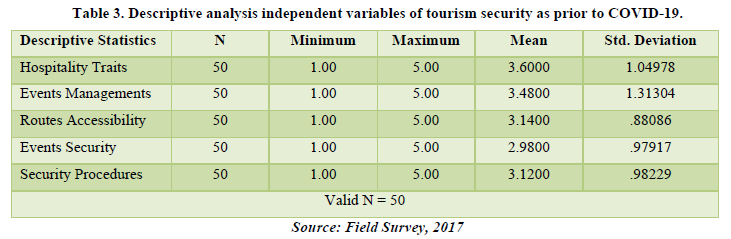

The table shows the responses of independent variables of tourism security as prior to COVID-19. In the first variable hospitality traits of tourism security as prior to COVID-19, 6% respondents strongly agreed and 54% respondents agreed. It shows than 76% responses above the value 3. In the second variable events managements, 12% of respondents strongly agreed and 36% of respondents agreed which holds 64% above the value of 3. In the third variable routes accessibility, 6% respondents strongly agreed and 24% agreed accounting only 44% above the value of 3. Similarly, in events security of 2% of respondent strongly agreed and 36% agree. This variable account 74% above the value of 3. In the last variable, security procedure 6% strongly agreed and 30% agreed accounting to 42% above the value of 3. The average value and standard deviation of the responses are shown in the Table 3 below.

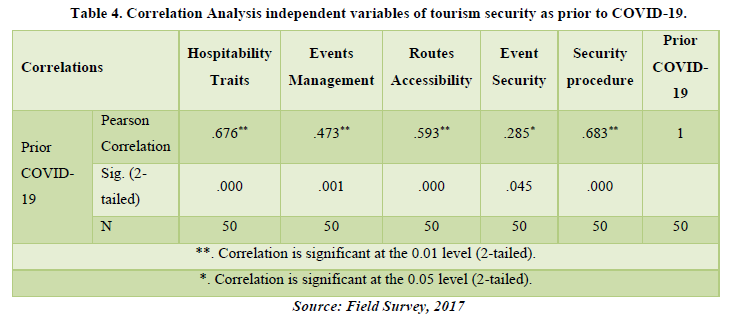

In the Table 3 mean and standard deviation of all the independent variables are shown. The mean responses of all variables range from 2.98 to 3.60. Among all the variables, hospitality traits have the highest mean value of 3.60 with standard deviation of 1.05 which means most of the respondent agreed that prior to the COVID-19 Nepal have extreme good hospitality traits with each other. The lowest standard deviation tends to be closer to the mean which shows more accuracy of data and comply with a perfect normal distribution. The mean value and standard deviation for event security are 2.98 and 0.98 respectively. This is the lowest mean value which indicates there is less event security among the tourism security as prior to COVID-19. The correlation analysis of independent variables of tourism security as prior to COVID-19 is shown in the table below (Table 4).

In the Table 4 the association between independent variables of tourism security as prior to COVID-19 is explained. The first variable, hospitality traits have a correlation coefficient of 0.676 with P-value of 0.00 which is less than 0.05. It means that hospitality traits are correlated at 1% Level of significant with tourism security as prior to COVID-19. Others independent variables, events management, routes accessibility and security procedure have a positive coefficient of with P- value of 0.01, 0.00 and 0.00 respectively which is less than 0.05. It means these all above four variables are correlated at 1% level of significant with tourism security as prior to COVID-19. But the P-value of event security is more than 0.05 which is not significant and is not correlated with tourism security as prior to COVID-19.

Result of Hypothesis 1

Since the P-value of all the independent variables (except event security) are less than 0.05 at 1% level of significant, there is association between Independent variables of tourism security as prior to COVID-19.

Tourism Security in post COVID-19

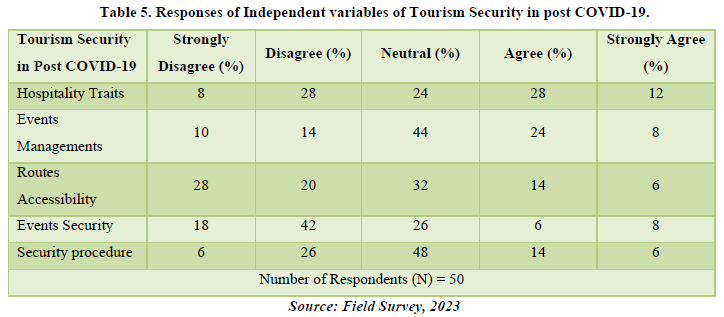

The variables are the determinant factors for the tourism security in post COVID-19 in Nepal are extracted from different literature review as mention above. The results of the responses are shown below (Table 5).

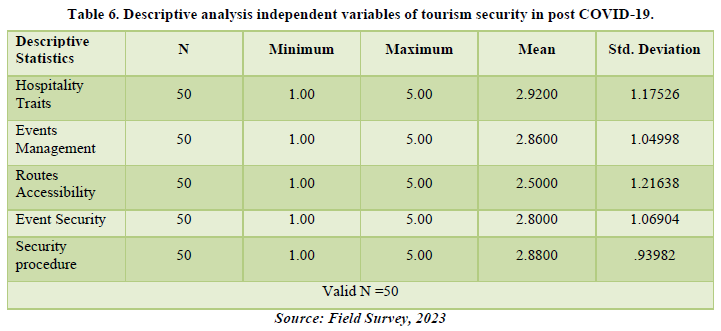

The Table 5 shows the responses of independent variables of tourism security in post COVID-19. In the first variable hospitality traits of tourism security in post COVID-19, 12% respondents strongly agreed and 28% respondents agreed. It shows than 64% responses above the value 3. In the second variable events managements, 8% of respondents strongly agreed and 24% of respondents agreed which holds 76% above the value of 3. In the third variable routes accessibility, 6% respondents strongly agreed and 14% agreed accounting 52% above the value of 3. But in the fourth variable events security, 8% of respondent strongly agreed and 6% agreed accounting only 40% above the value of 3. In the last variable, security procedure 6% strongly agreed and 14% agreed accounting to 68% above the value of 3. The average value and standard deviation of the responses are shown in the Table 6 below.

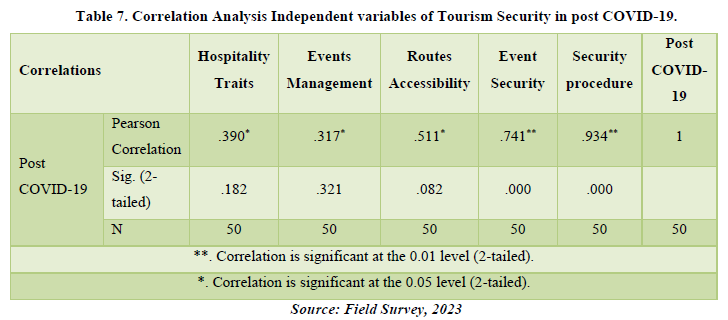

In the Table 6, mean and standard deviation of all the independent variables are shown. The mean responses of all variables range from 2.50 to 2.92. Among all the variables, hospitality traits have the highest mean value of 2.92 with standard deviation of 1.18 which means respondent agreed that in post COVID-19 Nepal have extreme good hospitality traits with each other. The lowest standard deviation tends to be closer to the mean which shows more accuracy of data and comply with a perfect normal distribution. The mean value and standard deviation for routes accessibility are 2.50 and 1.21 respectively. This is the lowest mean value which indicates there is less routes accessibility among the tourism security in post COVID-19. The correlation analysis of independent variables of tourism security in post COVID-19 is shown in the Table 7 below.

In the Table 7, the association between independent variables of tourism security in post COVID-19 is explained. The first variable, hospitality traits have a correlation coefficient of 0.390 with P-value of 1.82 which is more than 0.05. It means that hospitality traits are not correlated at 1% level of significant with tourism security in post COVID-19. Likewise, so, independent variables of events management and routes accessibility are also not correlated at 1% level of significant with tourism security in post COVID-19. But the independent variables of event security and security procedure have positive coefficient with P- value of 0.00 and 0.00 respectively which is less than 0.01. It means only two variables are correlated at 1% level of significant with tourism security in post COVID-19. The P-value of remaining three variables is more than 0.05 which is not significant and is not correlated with tourism security in post COVID-19.

Result of Hypothesis 2

According to the correlation analysis P-value of only two independent variables (except hospitality traits, event management and routes accessibility) are less than 0.01 at 1% level of significant which reflects tentatively reverse association lies in between independent variables of tourism security in post COVID-19.

Tourism Security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal

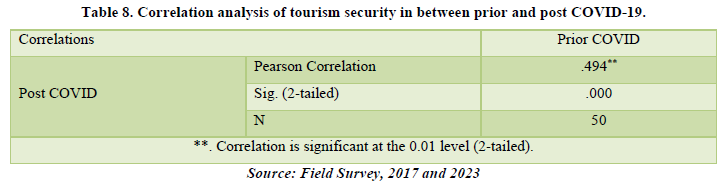

In order to test the relationship of tourism security in between prior and post COVID-19 in Nepal the correlation analysis is shown as below (Table 8).

The Table 8 shows the correlation analysis of tourism security as prior to COVID-19 and tourism security in post COVID-19 in Nepal. The P- value of Correlation coefficient is 0.00 which is less than 0.05 it is statically significant at 1% level of significant. The Correlation coefficient of tourism security as prior to COVID-19 and tourism security in post COVID-19 is 0.494. The results indicate that there is correlation with each other. Hence the final analytical findings could be explained on the basis of table as below.

Result of Hypothesis 3

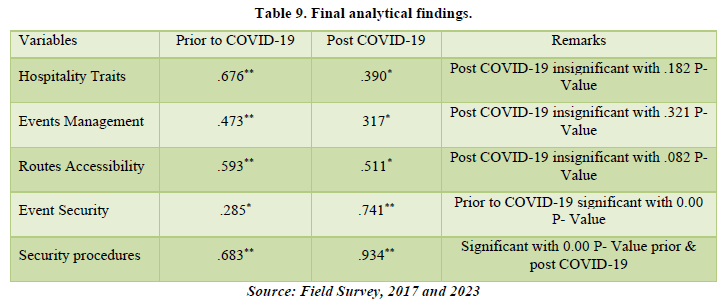

Since the P-value of tourism security as prior to COVID-19 and tourism security in post COVID-19 are less than 0.05 at 1% level of significant, there is significant variation (reverse association) of tourism security in between prior to COVID-19 and post COVID-19 in Nepal (Table 9).

According to the above Table 9 we can observe the variables hospitality traits, event management and routes accessibility of post COVID-19 are insignificant with P-value where the variable event security of prior to COVID-19 is significant with P-value. Regarding the variable security procedures as prior to COVID-19 and post COVID-19 is significant with both of them. On the basis of above mentioned remarks it is easily observed that the variables such as hospitality traits, event management and routes accessibility became degraded after the COVID -19 pandemic due to the new policies and regulations adopted by the Government as well as worldwide scenario. Whereas, event security seems significant as prior to COVID-19 pandemic due to security obligations. In the other hand, regarding the security procedures it maintained its aspects in both prior and post COVID -19 due to the rigorous security precautions.

CONCLUSION

Nepal is a small country with diverse socio-economic and physical features, drawing a wide spectrum of visitors worldwide to its preserved culture, variegated landscapes, snow-capped mountains and architectural wonders. These exquisite attractions of the country provide visitors a memorable experience. Tourism is a catalyst for stimulating economic, social and cultural activities and adds momentum to economic development. Tourism is an important catalyst in the socio-economic development in the modern times, contributing in multiple ways and strengthen the inter-connected processes. It is cited as a panacea for so many social evils such as underdevelopment, unemployment etc. in all the countries, especially in developing economies. The Findings of this study truly based on the association in between tourism stakeholders and tourism security sector which is formulated on the specific variables such as Tourism, COVID-19, Variation, Association and Security. As mentioned earlier, the primary objective of this paper was to explore the variation of tourism security in between prior and posts COVID-19 in Nepal in order to know the existing relationship and situation between them for the concrete conclusion and suggestions. As we conclude that, the aim of this paper is to analyze the variation of tourism security in between prior and posts COVID-19 in Nepal. The system of survey technique is applied in panels of tourism stakeholders and security personnel over the period of field survey 2017 and 2023. Employing tourism security as prior to and post COVID-19 variables, the results show that the relationship among all the sub-indexes of tourism security as prior to and post COVID-19 have variation (reverse association) as in Nepalese context, which strive for the further rational implementation in the days to come.

- Acharya, D., & Gurung, D. B. (2019). Crime and safety issues in tourism A case study of Nepal. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 7, 21-32.

- Adhikari, D. R., Adhikari, R., & Gautam, S. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on tourism industry A review of the literature. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8, 68-78.

- Adhikari, D. R., Rijal, K., & Giri, D. R. (2020). Tourist safety and security in Nepal: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8, 17-31.

- Aryal, B. R. (2002). Problems and Prospects of Tourism in Nepal. MA TU Kirtipur. Retrieved from: http://107.170.122.150:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/95/ShristiKarmacharyaThesis9881

- Aryal, D. (2005). Economic Impact of Tourism in Nepal. An Unpublished Master’s Thesis Submitted to the Tribhuvan University.

- Bach, S. & Pizam, A. (1996). Crimes in hotels. Hospitality Research Journal, Retrieved from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1096348096 02000205

- Bentley, T. (2006). Injuries to New Zealanders participating in adventure tourism and adventure sports. NZ Medical Journal, 119, 1-9.

- Buzan, B. (1991). New Patterns of Global Security in the Twenty First Century. International Affairs. Oxford Oxford University Press pp: 431-451.

- Chhetri, R.K. (2018). Tourism and Security in Nepal. Journal of Tourism & Adventure 1, 36-51.

- Dahal, B. M. (2007). Report on Peace and Press Vital Forces for Tourism Development. Kathmandu Nepal Travel Media Association (NTMA).

- Dev, K. (2010). Impact of Tourism Industry on the Economy of Nepal. Department of Economics University of North Bengal Darjeeling West Bengal India.

- DOT. (1972). Retrieved from: https://books.google.com.np/books?id=gUVLY3YOBq Cpg=PA25

- Fisher, D. (2004). The demonstration effect revisited. Annals of Tourism Research, 31, 428-446.

- German, J. & Gibson, S. (2007). Mobilizing Hospitality. Ashgate Publication Limited UK. Retrieved from: https://www.corwin.com/sites/default/files/upmbinaries/29171Jamal Chapter2.pdf

- George, R. (2003). Tourists perceptions of safety and security while visiting Cape Town. Journal of Tourism Management, 24, 575-585.

- Getz, D. (2007). Event Tourism Definition Evolution and Research. Retrieved from: www.sciencedirect.com

- Gurung, A. N., & Basnet, B. (2020). Terrorism and its impact on tourism in Nepal: An analysis of the past and present. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8, 18-29.

- Gurung, A. N., & Basnet, B. (2021). Tourism crisis management in the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of Nepal. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 9, 39-51.

- Hall, C.M. & O’ Sullivan, V. (1996). Tourism, Political Stability and Violence, in Pizam, A. &Mansfeld, Y. (Eds.), Tourism, Crime and International Security Issues 105-121. Chichester John Wiley & Sons.

- Iswani, N. (2006). Safety perception among tourist in eco-tourism area. Case Study: Pahang National Park. Unpublished Master Thesis Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Retrieved from: https://core.ac.uk/download /pdf/ 82304708.pdf

- Kunwar, R. R. & Pandey, R. N. (1995). Case study on the eff ects of tourism on culture and the environment: Nepal. Chitwan Sauraha and Pokhara Ghandruk, UNESCO.

- Kunwar, R. R. (2017). Tourists and Tourism: Revised and Enlarged Edition. Kathmandu: Ganga Sen Kunwar.

- Negi, J. M. (1990). Tourism Development and Resources Conservation. Metropolitan, New Delhi. Retrieved from: http://shodhganga.infl ibnet.ac.in/bitstream/ 10603/119504/9/09_chapter %201.pdf

- NTB. (2003). Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/ publication / 232876364_Tourism_in_Nepal.

- Pizam, A. &Mansfeld, Y. (1996). Tourism, crime and security issues. Chichester John Wiley & Sons.

- Pizam, A. &Mansfeld, Y. (1996). Toward a theory of tourism security. Chichester John Wiley & Sons.

- Paudyal, S. (1999). Factors Affecting Demand for Tourism in SAARC Region. An Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to the Department of Economics Faculty of Social Sciences BHU Varanasi, India.

- Pant, S., Kafle, S., & Gyawali, D. (2021). Tourists perception of natural hazards and safety in Nepal. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 9,1-14.

- Paudel, A. N., Karki, A., & Aryal, B. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and tourism in Nepal Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8, 47-60.

- Satyal, Y. R. (1988). A Geography of Tourism. London Mcpoland and Evans.

- Shrestha, H. P. (1998). Tourism Marketing in Nepal. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation Submitted to the Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu.

- Shrestha, P. M. (1999). Tourism in Nepal: Problems and Prospects. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Banaras Hindu University.

- Shrestha, H. P. (2000). Tourism in Nepal Marketing Challenges, New Delhi Nirala Publication.

- Tarlow, P. E., Wilks, J., Pendergast, D. &Leggat, P (2006). Crime and Tourism. In. Tourism in Turbulent Times Elsevier Amsterdam. pp: 93-106.

- Tarlow, P. E. (2014). Tourism security strategies for effectively managing travel risk & safety. Butterworth-Heinemann Publishers, UK. Retrieved from: https://www. elsevier.com/books/ tourism/tarlow/978-0-12-411570-5

- Theobald, J. (1997). The Act of Leaving and the Returning to the Original Starting Point. Unpublished Dissertation.

- Thio, S. (2005). Understanding Hospitality Activities: Social, Private, and Commercial Domain. Journal Manajemen Perhotelan, 1, 1-5.

- Upadhayaya, P. K. (2016). What Tourism Security Means for Nepal Journal of Tourism & Hospitality.

- Upadhayaya, P.K. & Upreti, B. R. (2013). Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, trends and future prospects for peace and prosperity. Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara, Nepal.

- Upadhayay, R.P. (2008). Rural Tourism to Create Equitable and Growing Economy in Nepal. Published-National Academy of tourism and Hotel Management (NATHMA) Kathmandu.

- W B (2016). Nepal World Bank Group Country Survey 2016. World Bank Group Washington D.C. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/nepal